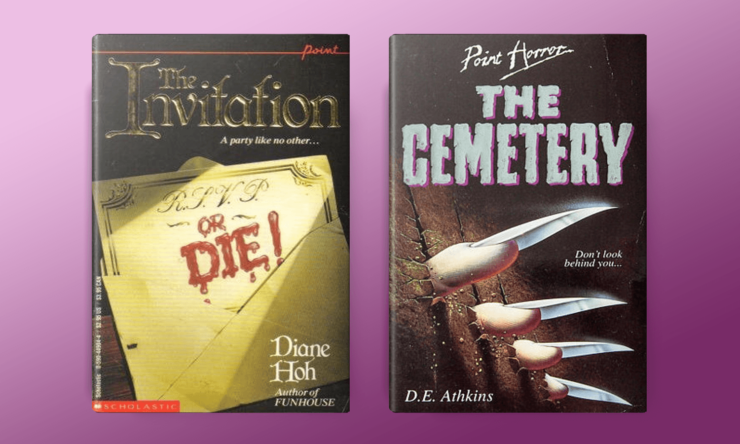

Point Horror novels are just bursting with fun fall traditions: costumes, tricks and treats, ominous invitations to socially-stratified parties where you just might end up murdered. In both Diane Hoh’s The Invitation (1991) and D.E. Athkins’ The Cemetery (1992), a group of unwitting teens are invited to the party of the season, only to end up finding themselves fighting for their lives.

(Also, can we take just a moment to recognize and appreciate the witty humor of the nom de plume of D.E. Athkins, which can also be read as Death-kins? This sounds both ominous and adorable, like a demonic puppy. Well played, Athkins).

While both The Invitation and The Cemetery feature parties of doom, the threats come from very different corners, demonstrating the wide range of ways that ‘90s teen horror kids can get themselves in serious trouble. In The Invitation, uber-mean girl Cass Rockham doesn’t see any problem with inviting a group of her unpopular peers to her party just to have them kidnapped and locked in secret locations around her massive estate, so that she and her guests can have a “people hunt.” Why settle for just a regular, boring old scavenger hunt if you can deprive others of their humanity, turn them into game pieces, and terrorize them for your own entertainment? As far as Cass has reasoned (which is admittedly not too far), they’re probably just excited to be part of the festivities at all. There’s obviously no other way that they would have been invited, so really, this is just the cost of being popularity-adjacent.

As if this weren’t horrific and exploitative enough, once the teens have been locked in their secret hiding places—alone, in the dark, and with video cameras trained on them so the other partygoers can enjoy their fear—someone else kidnaps them again, takes them to secondary locations, and actively tries to murder them. This attempted murderer turns out to be their new friend Shane’s old friend Lynn, who feels betrayed because Shane and her parents moved away after the two girls got in trouble for trying to steal a ring from a jewelry store. Lynn is filled with a murderous rage after being abandoned by Shane and shunned in her hometown, while Shane starts a new life and makes new friends, who obviously all must die because as Lynn says, “Shane doesn’t deserve friends.”

In this case, the biggest threat that teen girls face is other teen girls, who manipulate them, abuse them, and attempt to murder them. There’s a token guy in Shane’s new friend group (Donald), but he proves rather ineffectual and has to be rescued by the resourceful protagonist Sarah. Cass abuses them all and never really recognizes that she’s doing anything wrong, even after the ambulance has been called to rush the first of the injured “game pieces” to the hospital. Ellie’s sister Ruth is so jealous that Ellie was invited to Cass’s party and she wasn’t that she intentionally spills nail polish on Ellie’s beautiful new dress and Ellie has to go to the party wearing a dress that makes her look “like a fat clump of celery.” Ruth also torments Ellie as she gets ready, telling her that “You’re not going to have a good time … You don’t belong at that party, and you know it” in an adolescent echo of DePalma’s Carrie, with Carrie’s unhinged mama warning “they’re all going to laugh at you.”

Buy the Book

Where the Drowned Girls Go

Shane’s three new friends—Sarah, Maggie, and Ellie—are supportive of one another and, as the novel begins, of Shane as well. But when Shane’s “dark past” comes to light, Sarah seems to pump the brakes on this new friendship. She is instrumental in Shane’s rescue and doesn’t overtly reject Shane or shame her for her past misdeeds, but she also doesn’t comfort her, embrace her, or even help her up off the floor after her near-death experience and the trauma of watching Lynn fall to her death. Instead, she “shook her head and found that she had just enough energy left to give Shane a small grin,” which is … okay, I guess? Maybe. In a world where danger can take many forms, the most terrifying one is that of other teen girls, undermining readers’ sense of sisterhood, solidarity, or that they can expect to be treated humanely by their peers, in a dark amplification of high school social hierarchy.

While teen girls are the central horrors of The Invitation, in The Cemetery, the danger is more metaphysical, tying the teens of Point Harbor to a darker past, though it is definitely their own foolhardy choices that reawaken it. After the Halloween dance at school, the real party starts at the old cemetery, where an exclusive group of teens get together to drink, light a bonfire, tell ghost stories, have a makeshift séance, dance on top of mausoleums, and play hide and seek among the tombstones. At midnight. On the night of a full moon. No red flags or misguided choices there. Their revelries awaken some ancient evil, which is … well, Athkins isn’t really very clear on that. One of the horrors emerges from the grave of a woman named Charity Webster, which is an eerie non-coincidence, since that’s also the name of one of the terrorized teens (though contemporary Charity goes by the slightly unnerving nickname “Char”). The undead manifestation of this older Charity is angry because she was buried outside the official walls of the cemetery, shunned by her fellow townspeople because she had found a way to stop the supernatural being they refer to as the Ripper (the other central horror of The Cemetery). The Ripper seems to both possess people and also be able to take on their appearance to trick their friends. Where the Ripper came from and its reasons for murdering townspeople aren’t exactly clear, but in all the splatter-y horror, it doesn’t seem to really matter very much.

There’s also an odd new kid in town named Jones, who seems to know an awful lot about the Ripper, but whose backstory remains similarly unplumbed. The only explanation for his odd store of knowledge being “I found it in my travels.” (Travels where? Why? Does the Ripper pop up in different times and different places? How does he know about “the sulfur fires from the other side”?). We don’t know where he’s from, who he is, or even if he’s really a teenager (which raises a whole different set of creepy questions). When Char is trying to figure out what’s going on, Jones finds her in the library and slips an ancient diary into her bag, with its legends of doomed sailors, ghost ships, and coastal New England mystique potentially tying the Ripper to Point Harbor’s dark history. This quasi-historical contextualization of the Ripper provides little actual explanation or developed mythology, however. Jones seems to have been pursuing this evil for some time, so this purportedly geographical explanation is suspect. The Ripper could be connected to some physical object or could be animated by its urban legend status, able to spring to life anywhere at any time, raising all sorts of troubling possibilities for The Cemetery’s characters and for Athkins’ readers.

There are similarly mystery-solving narrative imperatives in both The Invitation and The Cemetery, but how those mysteries must be explored and who is revealed to be ultimately responsible are very different journeys. The Invitation starts out with a fairly standard scavenger hunt format (aside from the prizes being human beings, of course), though there’s a bait-and-switch as Sarah must not only find the original hiding places, but also follow clues to find where they were taken next, who moved them, and why. The teens of The Cemetery initially believe that the murderer stalking them is human and could even be one of their friends. And truthfully, they have plenty of reasons to think so. There’s a lot of subterfuge, betrayal, and potential violence between them even when they’re getting along and not suspecting one another of violent murder. Dade dates Cyndi, but is really interested in Jane, while Cyndi used to date Wills, who is now going out with her best friend Lara. Rick dresses as a bloody ax-wielding Santa Claus for Halloween and torments his funeral director father with tasteless jokes about death and dying, and brother and sister Dorian and Cyndi actually each tried to murder the other when they were children (and their parents’ response wasn’t intense psychotherapy but rather to simply move them to opposite wings of the house, to keep them safe from one another).

Unlike many books in the ‘90s teen horror tradition that marginalize any representation of sex or drug use, these characters are sexually active and enjoy illicit substances. In the opening chapter, Cyndi reminds Lara that “there are other things besides kissing” and we learn that Georgie “liked being high.” These are not innocent boys and girls on the cusp of adolescence who find themselves in inexplicable danger: they are teens who are making plenty of bad choices, doing lots of things their parents wouldn’t approve of, and are pretty actively looking for the trouble they find. Once the party starts, the teens seem more likely to give into peer pressure, let their inhibitions go, and behave in ways they wouldn’t outside of this bacchanalian context as they drink, abuse their peers, and desecrate graves, all actions which result in vengeance and horror. When the trouble actually shows up, though, it’s really nothing like what they expected and as a result, their responses aren’t particularly well-reasoned or effective. Georgie’s go-to move, for example, is to return to the scene of Wills’s violent murder to ostensibly look for clues, though her real driving motivation is to have some hot horror sex with Dorian … which ends with her getting murdered and Dorian fleeing in terror, with an urban legend-esque hook hanging from one of his car’s door handles, presumably made corporeal as a result of the ghost stories they told in the cemetery on Halloween night. In the end, friendship (kind of) saves them and the Ripper is once again laid to rest, though there’s no real reassurance that this rest will be enduring or easy.

As outlandish as these particular horrors may be, one uniting factor between The Invitation and The Cemetery that resonated with teen readers was the central position of class and social status. The teens in both of these books are acutely aware of how their class position is perceived and how it shapes their interactions with others. The Invitation’s Cass Rockham and The Cemetery’s Cyndi Moray come from wealthy families. While this wealth is coded as morally suspect in some ways—both girls’ parents are disengaged and not terrifically interested in what their children are up to, with Cass’s parents on an extended vacation in France when she throws her party and Cyndi’s dad offering the boys drinks before they head out to drive to the dance—this wealth provides them a good deal of power and prestige among their peers. The characters who are most likely to be excluded, abused, or murdered in both books are less socially privileged, a fact which is commented upon by both the authors and the characters’ peers, as is the case with the whole cast of “people hunt” misfits in The Invitation and with party-crasher Georgie in The Cemetery.

Even those who are on more equal social ground with their hostesses are leery of invoking their rage. The majority of the teens at Cass’s party are afraid to say no to her, acquiescing when she demands that they play musical chairs and willing to go along with her “people hunt” plan, unsettled but feigning enthusiasm in order to avoid Cass’s ire. Similarly, as odd as the party at Cemetery Point is, the majority of the teens go along with it because Cyndi has planned it, telling her peers what to do (even when she imperiously commands them to dance), where to set things up, and how the night will go, threatening to exile anyone who fails to comply. One of the first descriptions Athkins offers of Cyndi in the opening chapter is that “Cyndi liked to push people. See what she could make them do.” In both cases, the other characters are hyper-aware of Cass and Cyndi’s judgement, keeping one eye out to see what they’re doing, what they think of the others, and what the potential ramifications of displeasing them might be. Georgie and Dorian are the only characters in The Cemetery who challenge Cyndi’s micromanaging of her social group, crashing the party and becoming targets for Cyndi’s anger, bullying, and personal attacks, including her public slut-shaming of Georgie. While Cyndi herself is not responsible for her peers’ deaths, Georgie and Dorian are two of those who get murdered, aligning Cyndi’s judgment with that of the Ripper, as those who are considered “outsiders” become monster’s victims.

While there are a handful of characters who stand up to these queen bees—like Sarah and her bland, popular guy love interest Riley in The Invitation—for the majority of their peers, the threat of social marginalization keeps them silent and submissive. This group dynamic heightens teen readers’ own anxieties, experiences of exclusion and bullying, and fear of social irrelevance. While it’s easy for adults—including parents of those teen readers—to say that it doesn’t matter what others think and talk about the importance of resisting peer pressure, echoing the “just say no” ethos of the Reagan ‘80s, the novels of the 1990s teen horror cycle foreground these teens’ experiences and their frequent inability to say no or resist their more domineering peers. For example, in The Invitation, why on earth would Ellie follow a stranger into the woods and into a dark building, allowing herself to be locked up without a fight? Well, she doesn’t want to be a killjoy or the one who “can’t take a joke,” she still somehow feels honored to have been included in the party, and she doesn’t want to anger Cass, validating Cass’s social machinations and sense of superiority. This is nonsensical and literally puts her life in danger, but the pressures of acceptance and belonging for these teens are overwhelming, overriding everything else.

In the end, it is the characters who do find a way to say no who become self-actualized, define their identities clearly outside of this peer group dynamic, and survive, a potentially reassuring message for teen readers about the importance of being true to oneself, no matter the cost. In The Invitation, while Sarah doesn’t actively resist being taken and locked in a secret room by one of Cass’s minions, she is the first to break out and almost immediately begins working to rescue her friends. While Riley, Sarah’s love interest, is largely unremarkable, he also stands up against Cass, willing to risk his popularity and social status to do what’s right and help Sarah save her friends. Sarah and Riley are temporarily joined by two willing accomplices, though one inexplicably wanders off part way through and the other turns out to be the attempted murderer in disguise, so you can’t always trust your fellow would-be rebels. But in the end, Sarah reaches out to hold Riley’s hand (in lieu of going to help her friend Shane up off the floor following her near-murder, which really puts priorities in perspective for Hoh’s young readers).

The joys of resistance are less straightforward in The Cemetery, since Georgie and Dorian—the two teens who were most resistant to Cyndi’s manipulation—are among those violently murdered by the Ripper, but Char sees the supernatural reality on the other side of Point Harbor, lives to tell the tale, and in the end, decides that while she really likes her friends, she exists as an individual separate from them and doesn’t need their constant validation. When Char’s surviving friends invite her and Jones to come over, she tells them they’ll stop by later, but for the moment is just fine on her own with Jones. This isn’t a fully independent self-actualization—and may actually just fit the standard heteronormative pattern of a teen girl choosing romance over friendships or other platonic relationships—but given the stratified social hierarchy of their friend group and everyone’s earlier subservience to Cyndi, it is pretty significant that Char is able to temporarily turn her friends away, engage with those relationships on her own terms, and start overtly thinking about who she is, what she wants, and the questions she has.

While one on level, The Invitation and The Cemetery are fairly straightforward horror tales, full of mystery, intrigue, and murder, on another level, they map the complicated and dangerous terrain of teen social relationships. Class matters, even among the high school set, and the teens with money are often the teens with power, including the power to manage and manipulate their peers. Characters struggle to say no to the queen bees, even when they know they should or when remaining silent compromises their moral judgment or puts their very lives in danger. For ‘90s teen horror readers, the social landscape of high school was a complicated, high stakes endeavor, where the right clothes or an invite to the “popular” party were crucial, but as Hoh and Athkins remind them, if the invitation seems too good to be true, you’re probably about to be murdered.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.